A quantidade de material (não só sobre a WW1) disponível no site Old Magazine Articles é no mínimo desnorteante.

The First World War had only been raging for six months when this article first appeared in a 1915 issue of THE NEW REPUBLIC. As the journalist makes clear, one did not have to have an advanced degree in history to recognize that this war was unique; it involved almost every wealthy, industrialized European nation and their far-flung colonies; thousands of men were killed daily and many more thousands stepped forward to take their places. The writer recognized that this long anticipated war was an epic event and that, like the French Revolution, it would be seen by future generations as a marker which indicated that all changes began at that point.

THE NEW REPUBLIC

January 2, 1915

1914 - The end of an era?

(Frank H. Simonds)

In its immediate effects upon the lives and fortunes of millions of men and women, the great war is unmistakably the largest human fact since the French Revolution. Since that tremendous deluge overflowed the frontiers of the Old Monarchy and began its resistless march from Paris to Moscow, from the Straits of Dover to the Syrian Coast, there has been no single disturbance of the whole system of nations and continents comparable with that which is now going on before our eyes.

Yet in the face of this almost limitless destruction there is patent on many sides a disposition to regard it as an accident, a piece of collective insanity on the part of races and nations certain to be followed presently by a sad return to sanity. Those who were but a few months ago assuring us that there never could be another general war are most vociferously informing the same audience that this will be the last. In the same sense there is the general tendency to assert that when it has come to an end we shall be as we were before, that after a temporary if terrible interruption nations and continents will return to the same tasks, the same ideas, the same ideals which they followed up to the fatal first of August, 1914.

Going back to the French revolution, is it not quite as clear from any reading of contemporary comment that a similar expectation prevailed everywhere save in Paris when the Allies at last undertook the little "police expedition" into France which was to bring the French people to their senses, restore a Bourbon to the throne, an aristocracy to control? Was it not quite as inevitable in the minds of those who directed the first invasion of France, which terminated at Valmy, that in a brief time the world was to be exactly as it had been before 1789, as it is now to many minds, that the treaty of peace which closes the present chapter will send the world back to the precise point from which it started on this temporary explosion of madness?

Accepting this as possible, is it inevitable? Is it not a possibility that what is taking place marks quite as complete a bankruptcy of ideas, systems, society, as did the French Revolution? For Carlyle, in many ways the most satisfactory interpreter of the French Revolution, it was above all else a conflagration, a burning up of shams, of inveracities, a forest fire sweeping through woods long dead and become tinder, a total dissolution of a world which had become unreal, inveracious, devitalized.

Now it is at least plain that the very fact of a world war is a negation of all that the contemporary generation has believed, has accepted, has asserted. As a final evidence of the stability of the order existing before the war, we have been accustomed to point to at least four bulwarks, each a product of contemporary genius, each a prop and promise of the perpetuation of what was frankly conceded to be the best and the wisest social order ever devised by the mind of man. These four forces may be described as science, sentiment, high finance and socialism.

As to science, it will be remembered that twenty years ago M. Bloch quite convinced a willing world that war had become impossible because modern weapons had made the cost of battle beyond the resource of men or nations to pay. In that time the world eagerly read carefully prepared tables which showed that, given the power of modern artillery and rifle, battles would now be more terrible than any known to history. From this fact it was reasoned that men would not fight, nations would not dare to send their citizens to battle. Yet after twenty years it was fully demonstrated in the Balkan War that all the terrible destructiveness of modern weapons did not prevent men from fighting, and from fighting hand to hand. It was the bayonet and not the artillery which decided Monastir and Kirk Killisse. The Bulgarian "Na noge" was still the watchword of battle, and the knife terrible in European warfare as in African. Today each report of battle brings the details of bayonet charges comparable with those that made Gettysburg famous and Waterloo immortal. Thus science, which in twenty years has added much to the terrors foreseen by M. Bloch, has given us the 42-centimetre gun and the French "75" has in no degree weakened the spirit of man. As the Greeks, the Romans, the fighting races of all past time fought, so the great nations of twentieth century Europe are fighting. Science has made war more terrible, more costly, but it has not made war impossible, filled man with controlling terror. Thus it has failed.

Is it less plain that sentiment, the sentiment that was behind The Hague Conferences, the international arrangements, the endless "scrap of paper" and agreements, the indefinable thing we call humanitarian spirit, has failed quite as completely? It did not avail to prevent the invasion of Belgium, the laying in waste of East Prussia. Has there been any time since the Thirty Years' War when the map of Europe could show so many regions devasted, so many millions homeless, destitute? Has war ever been more horrible in its manifestations than this time, when the ashes of Louvain, the ruins of Belgium, Polish, Galician, French, and Prussian towns lie before a world? Has war ever been more dreadful than now, when we count in Germany alone not less than 1,500,000 men killed and wounded in five months? Yet in any nation at war is there any present agitation for peace?

High finance failed in the last week of July. Everyone remembers how, in the last days before shooting began, there was of a sudden a flurry in all the world of finance, a sudden report that at last the men who were the masters of millions had served their ultimatum on statesmen, threatened, commanded, bullied. That little interruption had its climax on July thirty-first. But on August first Germany declared war on Russia, and before the following week was over, the battle lines stretched straight across the Continent. There never was anything more complete, more decisive than the defeat of world finance when it undertook to take the helm in storm.

Last of all there was socialism. Ten years ago it was the fashion to believe that socialism, with its annex of internationalism, had quite permeated and conquered Europe. French and German workmen, faced by battle, were to ground their arms and fraternize. Bebel and Jaurès were to succeed Bismarck and William II. All France was in the hands of the socialists, the flag was on the dunghill, and the army was in disgrace. Pelletan was telling Frenchmen that a navy was of use merely as a school. Jaurès was describing an armed citizenry as the outside limit of legitimate self-defense, ideas strangely familiar to American ears just now.

Yet when the war came, instead of fraternization a Frenchman shot Jaurès; a socialist became the greatest French War Minister since the elder Carnot; Jules Guesde entered the ministry in France, Vandervelde in Belgium. The workmen of Moscow, on a strike which was mounting rapidly toward rebellion, voluntarily went back to work. The socialists in the Reichstag voted the war funds, and French socialists went to the battle line frankly affirming their desire to atone with their lives for their share in disarming France.

In sum, socialism, like all the other props, broke down instantly, and today no socialist ventures to say with assurance whether the end of the war will leave socialism a forgotten thing or place it on the seat of power; but all socialists recognize that the temper and the spirit of the men who are now fighting a great struggle holds out little present promise of any return to old pathways and ante-bellum ideals.

It is wholly possible that when at last peace comes, it will be proven that this war was the great accident most men now bold it, an illogical and unrelated interruption of the course of human ideas and ideals, all correctly established and asserted before 1914. But is it not quite as possible that a whole new order of ideas, ideals, perhaps a religious awakening, probably a new outburst of national spirit and patriotism in all races, may come? "All the king's horses and all the king's men" could not set the old order up again after the French Revolution; may it not be as impossible after this great war? May not 1914, like 1789, mark in human history the end of an era?

Fonte:

http://oldmagazinearticles.com/Why_was_1914_the-End_of_an_Era

|

THE NEW REPUBLIC

January 2, 1915

1914 - The end of an era?

(Frank H. Simonds)

In its immediate effects upon the lives and fortunes of millions of men and women, the great war is unmistakably the largest human fact since the French Revolution. Since that tremendous deluge overflowed the frontiers of the Old Monarchy and began its resistless march from Paris to Moscow, from the Straits of Dover to the Syrian Coast, there has been no single disturbance of the whole system of nations and continents comparable with that which is now going on before our eyes.

Yet in the face of this almost limitless destruction there is patent on many sides a disposition to regard it as an accident, a piece of collective insanity on the part of races and nations certain to be followed presently by a sad return to sanity. Those who were but a few months ago assuring us that there never could be another general war are most vociferously informing the same audience that this will be the last. In the same sense there is the general tendency to assert that when it has come to an end we shall be as we were before, that after a temporary if terrible interruption nations and continents will return to the same tasks, the same ideas, the same ideals which they followed up to the fatal first of August, 1914.

Going back to the French revolution, is it not quite as clear from any reading of contemporary comment that a similar expectation prevailed everywhere save in Paris when the Allies at last undertook the little "police expedition" into France which was to bring the French people to their senses, restore a Bourbon to the throne, an aristocracy to control? Was it not quite as inevitable in the minds of those who directed the first invasion of France, which terminated at Valmy, that in a brief time the world was to be exactly as it had been before 1789, as it is now to many minds, that the treaty of peace which closes the present chapter will send the world back to the precise point from which it started on this temporary explosion of madness?

Accepting this as possible, is it inevitable? Is it not a possibility that what is taking place marks quite as complete a bankruptcy of ideas, systems, society, as did the French Revolution? For Carlyle, in many ways the most satisfactory interpreter of the French Revolution, it was above all else a conflagration, a burning up of shams, of inveracities, a forest fire sweeping through woods long dead and become tinder, a total dissolution of a world which had become unreal, inveracious, devitalized.

Now it is at least plain that the very fact of a world war is a negation of all that the contemporary generation has believed, has accepted, has asserted. As a final evidence of the stability of the order existing before the war, we have been accustomed to point to at least four bulwarks, each a product of contemporary genius, each a prop and promise of the perpetuation of what was frankly conceded to be the best and the wisest social order ever devised by the mind of man. These four forces may be described as science, sentiment, high finance and socialism.

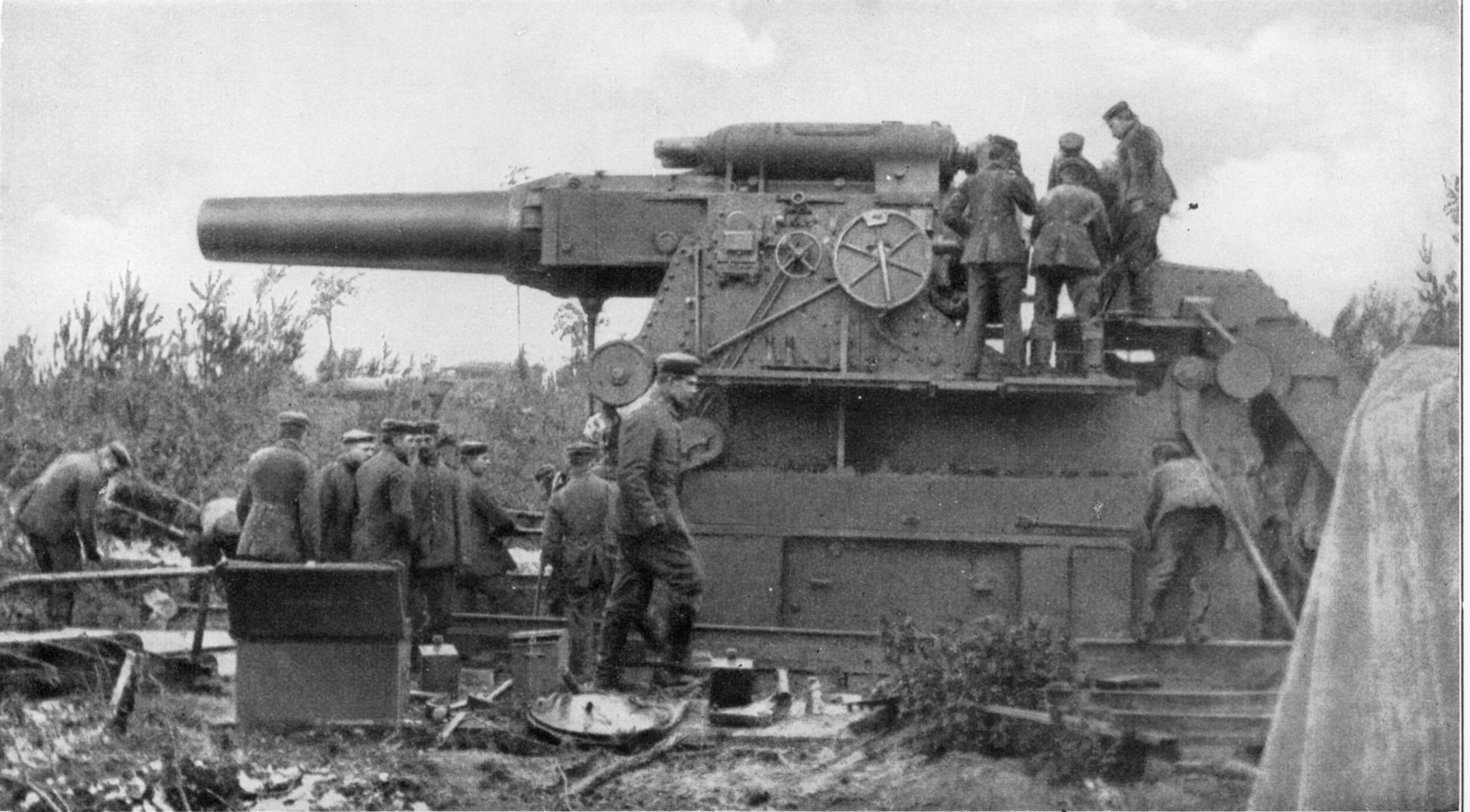

As to science, it will be remembered that twenty years ago M. Bloch quite convinced a willing world that war had become impossible because modern weapons had made the cost of battle beyond the resource of men or nations to pay. In that time the world eagerly read carefully prepared tables which showed that, given the power of modern artillery and rifle, battles would now be more terrible than any known to history. From this fact it was reasoned that men would not fight, nations would not dare to send their citizens to battle. Yet after twenty years it was fully demonstrated in the Balkan War that all the terrible destructiveness of modern weapons did not prevent men from fighting, and from fighting hand to hand. It was the bayonet and not the artillery which decided Monastir and Kirk Killisse. The Bulgarian "Na noge" was still the watchword of battle, and the knife terrible in European warfare as in African. Today each report of battle brings the details of bayonet charges comparable with those that made Gettysburg famous and Waterloo immortal. Thus science, which in twenty years has added much to the terrors foreseen by M. Bloch, has given us the 42-centimetre gun and the French "75" has in no degree weakened the spirit of man. As the Greeks, the Romans, the fighting races of all past time fought, so the great nations of twentieth century Europe are fighting. Science has made war more terrible, more costly, but it has not made war impossible, filled man with controlling terror. Thus it has failed.

Is it less plain that sentiment, the sentiment that was behind The Hague Conferences, the international arrangements, the endless "scrap of paper" and agreements, the indefinable thing we call humanitarian spirit, has failed quite as completely? It did not avail to prevent the invasion of Belgium, the laying in waste of East Prussia. Has there been any time since the Thirty Years' War when the map of Europe could show so many regions devasted, so many millions homeless, destitute? Has war ever been more horrible in its manifestations than this time, when the ashes of Louvain, the ruins of Belgium, Polish, Galician, French, and Prussian towns lie before a world? Has war ever been more dreadful than now, when we count in Germany alone not less than 1,500,000 men killed and wounded in five months? Yet in any nation at war is there any present agitation for peace?

High finance failed in the last week of July. Everyone remembers how, in the last days before shooting began, there was of a sudden a flurry in all the world of finance, a sudden report that at last the men who were the masters of millions had served their ultimatum on statesmen, threatened, commanded, bullied. That little interruption had its climax on July thirty-first. But on August first Germany declared war on Russia, and before the following week was over, the battle lines stretched straight across the Continent. There never was anything more complete, more decisive than the defeat of world finance when it undertook to take the helm in storm.

Last of all there was socialism. Ten years ago it was the fashion to believe that socialism, with its annex of internationalism, had quite permeated and conquered Europe. French and German workmen, faced by battle, were to ground their arms and fraternize. Bebel and Jaurès were to succeed Bismarck and William II. All France was in the hands of the socialists, the flag was on the dunghill, and the army was in disgrace. Pelletan was telling Frenchmen that a navy was of use merely as a school. Jaurès was describing an armed citizenry as the outside limit of legitimate self-defense, ideas strangely familiar to American ears just now.

Yet when the war came, instead of fraternization a Frenchman shot Jaurès; a socialist became the greatest French War Minister since the elder Carnot; Jules Guesde entered the ministry in France, Vandervelde in Belgium. The workmen of Moscow, on a strike which was mounting rapidly toward rebellion, voluntarily went back to work. The socialists in the Reichstag voted the war funds, and French socialists went to the battle line frankly affirming their desire to atone with their lives for their share in disarming France.

In sum, socialism, like all the other props, broke down instantly, and today no socialist ventures to say with assurance whether the end of the war will leave socialism a forgotten thing or place it on the seat of power; but all socialists recognize that the temper and the spirit of the men who are now fighting a great struggle holds out little present promise of any return to old pathways and ante-bellum ideals.

It is wholly possible that when at last peace comes, it will be proven that this war was the great accident most men now bold it, an illogical and unrelated interruption of the course of human ideas and ideals, all correctly established and asserted before 1914. But is it not quite as possible that a whole new order of ideas, ideals, perhaps a religious awakening, probably a new outburst of national spirit and patriotism in all races, may come? "All the king's horses and all the king's men" could not set the old order up again after the French Revolution; may it not be as impossible after this great war? May not 1914, like 1789, mark in human history the end of an era?

Fonte:

http://oldmagazinearticles.com/Why_was_1914_the-End_of_an_Era