Nada de novo no front

Trechos de Nada De Novo No Front (1929), de Erich Maria Remarque.

A guerra foi um dilúvio que nos arrastou. Para os outros, para os mais velhos, ela foi apenas um intervalo: conseguem pensar no tempo que virá depois. Mas nós fomos apanhados por ela, e não sabemos o fim de tudo isto. Apenas sabemos, por hora, que nos embrutecemos, de uma maneira estranha e dolorosa, mesmo que muitas vezes nem sequer fiquemos tristes.

- - -

Kat olha o céu, solta um peido sonoro e diz, pensativo:

- Cada feijãozinho dá o seu sonzinho.

Kat e Kropp começam a discutir. Ao mesmo tempo apostam uma cerveja para ver quem acerta o vencedor de um combate de aviões que está se travando neste momento acima de nós.

- - -

Kropp, ao contrário, é um pensador. No seu entender, uma declaração de guerra deve ser uma espécie de festa do povo, com entradas e músicas, como nas touradas. Depois, os ministros e os generais dos dois países deveriam entrar na arena de calção de banho e, armados de cacetes, investirem uns sobre os outros. O último que ficasse de pé seria o vencedor. Seria mais simples e melhor do que isto aqui, onde quem luta não são os verdadeiros interessados.

- - -

Os gritos continuam. Não são homens, eles não gritam assim tão horrivelmente. Kat diz:

- Cavalos feridos.

Eu nunca tinha ouvido cavalos gritarem e quase não posso acreditar. É toda a lamentação do mundo, é a criatura martirizada, é uma dor selvagem, terrível, que assim geme. Ficamos pálidos. Detering levanta-se.

- Pelo amor de Deus, acabem logo com eles!

É lavrador e conhece os cavalos muito bem. Isto toca-lhe fundo. E, como se fosse de propósito, o fogo quase cessa, fazendo ficar mais nítido o gritar dos bichos.

- - -

Os primeiros minutos com a máscara decidem sobre a vida ou a morte: toda a questão reside em saber se será impermeável. Evoco as imagens terríveis do hospital: homens atingidos pelo gás que, durante dias seguidos, vomitam, pouco a pouco, os pulmões queimados.

Respiro com cuidado, a boca apertada contra a válvula. Agora, o lençol de gás atinge o chão e insinua-se em todas as depressões. Como uma medusa enorme e flácida, espalha-se por todos os cantos ao penetrar em nossas trincheiras.

- - -

- Aí eu agarraria uma coisa robusta assim, uma cozinheira boa, sabe, com bastante coisa para segurar, e nada mais a não ser... cama! Imaginem só, camas de verdade com edredons e colchões; meus filhos, durante oito dias garanto que não vestiria uma calça!

Todos silenciam. A imagem é por demais maravilhosa. Arrepios correm-nos pela pele.

- - -

De qualquer maneira, vai ser difícil para nós. Será que lá em casa eles não se preocupam, às vezes, com isto? Dois anos de tiros e granadas... não é algo que se pode despir, como uma roupa.

- - -

Kat depena e prepara o ganso. Colocamos as penas cuidadosamente de lado. Com elas, pretendemos fazer pequenos travesseiros com os dizeres: "Descansem em paz sob o bombardeio".

- - -

A frente é uma jaula, dentro da qual a gente tem de esperar nervosamente os acontecimentos. Estamos deitados sob a rede formada pelos arcos das granadas, e vivemos na tensão da incerteza. Acima de nós, paira a fatalidade. Quando vem um tiro, posso apenas esquivar-me e mais nada; não posso adivinhar exatamente onde vai cair, nem influir em sua trajetória.

- - -

Os ratos aqui são particularmente repugnantes, pelo seu grande tamanho. É o tipo que se chama "ratazana de cadáver". Têm caras horríveis, malévolas e peladas. Só de ver seus rabos compridos e desnudos nos dá vontade de vomitar.

No setor vizinho, os ratos atacaram, morderam e roeram dois grandes gatos e um cachorro até matá-los.

- - -

Na verdade, a baioneta já perdeu praticamente sua importância. Durante o ataque, a moda agora é avançar só com granadas de mão e uma pá.

- - -

Amanhece sem que nada aconteça - apenas este rolar incessante, por trás das linhas inimigas, que acaba com os nervos; são trens, trens e mais trens, caminhões e mais caminhões. Que está-se concentrando do outro lado? Nossa artilharia dispara sem cessar na sua direção, mas o movimento não acaba, não tem fim.

- - -

O primeiro dos rapazes parece ter efetivamente enlouquecido. Corre e bate com a cabeça na parede como um bode, quando consegue soltar-se.

- - -

Um jovem francês fica para trás e é alcançado pelos nossos. Levanta as mãos: numa delas ainda segura o revólver. Não se sabe se ele quer atirar ou render-se; um golpe de pá abre-lhe o rosto ao meio. Um outro vê a cena e tenta fugir, mas, um pouco adiante, uma baioneta é enterrada em suas costas como um raio.

- - -

Kat dá coronhadas no rosto de um dos atiradores da metralhadora, que ainda não fora ferido, até amassá-lo. Os demais, nós matamos a baioneta, antes de poderem servir-se das granadas de mão. Depois, bebemos, sedentos, a água de refrigeração da metralhadora.

- - -

Não precisamos, porém, nos preocupar [com os mortos]: são enterrados pelas granadas. Alguns têm as barrigas inchadas como balões, assobiam, arrotam e mexem-se. São os gases que se agitam neles.

- - -

Gostamos dos aviões de combate, mas detestamos como a peste os de observação, porque atraem para nós o fogo da artilharia. Poucos minutos depois de surgirem, explode um dilúvio de granadas. Com isto, perdemos onze homens num só dia, inclusive cinco enfermeiros. Dois ficaram tão esmagados, que Tjaden afirmou poder raspá-los da parede da trincheira com uma colher, e enterrá-los nas marmitas.

- - -

Procuro dominar-me e acompanho minha irmã ao açougue, para comprar uma libra de ossos. Isto é um grande luxo, e já de manhã cedo faz-se uma fila para esperá-los. Muitos chegam a desmaiar.

Não temos sorte: depois de termos esperado, revezando-nos, durante três horas, a fila se dispersa. Os ossos acabaram. Foi bom ter recebido minhas rações. Levo-as para minha mãe, e, assim, nós todos temos comida mais substancial.

- - -

Fico frequentemente de sentinela, vigiando os [prisioneiros] russos. Na escuridão, vêem-se os seus vultos se moverem como cegonhas doentes, como enormes pássaros.

- - -

- Mas, do outro lado, mentem mais do que nós - replico. - Lembrem-se dos panfletos que encontramos entre os prisioneiros, afirmando que comíamos as crianças belgas. Os patifes que escrevem estas coisas deveriam ser enforcados. Estes é que são os verdadeiros culpados!

- - -

Nos parapeitos, estão alguns atiradores de elite. Têm fuzis com miras telescópicas, e examinam o setor inimigo. De vez em quando, ouvem-se tiros e, de repente, exclamações:

- Bem no alvo!

- Viu o salto que ele deu?

- - -

Chegaram muitos reforços ingleses e americanos. Têm muito corned beef e farinha de trigo branca; muitas armas novas e muitos aviões. Mas nós, pelo contrário, estamos magros e famintos. Nossa comida é tão ruim e adulterada com tantos sucedâneos que ficamos doentes. As latrinas estão sempre cheias de gente.

- - -

Nossa artilharia está no fim... tem pouca munição... e os canos estão tão gastos que os tiros não são certeiros e atingem nossos próprios soldados. Temos poucos cavalos, nossas tropas novas compõem-se de rapazes anêmicos, que precisam de cuidados, que não conseguem carregar mochilas, mas que sabem simplesmente morrer aos milhares. Nada conhecem de guerra, apenas avançam e deixam-se derrubar. Um único aviador divertiu-se exterminando duas companhias de recrutas como estes, quando acabavam de sair do trem, antes mesmo de terem ouvido falar em abrigo.

- - -

Pode-se levar um tiro e morrer, pode-se ser ferido e recolhido ao Hospital Militar mais próximo. Se não nos amputam um membro, caímos mais cedo ou mais tarde nas mãos de um destes cirurgiões que, com a Cruz de Ferro na lapela, nos diz:

- O quê? Só porque esta perna é um pouco mais curta do que a outra? Nas trincheiras você não precisa correr, se for corajoso. Este homem está apto para o serviço. Retire-se!

- - -

Os tanques, antes objeto de troça, transformaram-se em armas terríveis. Desenvolvem-se em longas filas blindadas, e, aos nossos olhos, personificam, mais do que qualquer coisa, o horror da guerra.

- - -

Os boatos falsos e perturbadores de um armistício e de paz brotam no ar e sobressaltam os corações, tornando mais difícil do que nunca a volta para a linha de frente!

- - -

Não somos vencidos, pois, como soldados, somos melhores e mais experientes; somos, simplesmente, esmagados e repelidos pela enorme superioridade de forças.

Mais:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ciq9ts02ci4

THE AMERICAN SCHOLAR

March 2, 2011

In World War I, nearly as many British men refused the draft - 20,000 - as were killed on the Somme's first day. Why were those who fought for peace forgotten?

(Adam Hochschild)

An early autumn bite is in the air as a late, gold-tinged afternoon falls over the rolling countryside of northern France. Where the land dips between gentle rises, it is already in shadow. Dotting the fields are machine-packed rolls of the year's final hay crop. Up a low hill, a grove of trees screens the evidence of another kind of harvest reaped on this spot nearly a century ago. Each gravestone in the small cemetery has a name, rank, and serial number; 162 have crosses and one has a Star of David. When known, a man's age is engraved on the stone as well: 19, 22, 23, 26, 34, 21, 20. Ten of the graves simply say, "A Soldier of the Great War, Known unto God." Almost all the dead are from Britain's Devonshire Regiment, the date on their gravestones July 1, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Most were casualties of a single German machine gun several hundred yards from this spot, and were buried here in a section of the frontline trench they had climbed out of that morning. Some 21,000 British soldiers were killed or fatally wounded that summer day, the day of greatest bloodshed in the history of their country, before or since.

From a nearby hilltop, you can see a half dozen of the 400 cemeteries where British soldiers are buried in the Somme battlefield region, a rough crescent of territory less than 20 miles long, but graves are not the only mark the war has made on the land. More than 700 million artillery and mortar rounds were fired on the Western Front between 1914 and 1918, and many failed to explode. Every year these leftover shells kill people. Dotted through the region are patches of uncleared forest or scrub surrounded by yellow danger signs in French and English warning visitors away. More than 630 bomb-disposal specialists have been killed in France since 1946. Like those shells, the First World War itself has remained in our lives, below the surface, because we live in a world so much formed by it.

The war's destructiveness still seems beyond belief. In addition to the dead, another 36,000 British troops were wounded on the first day of the Somme offensive. But worse was yet in store. "No, we do not pardon," Adolf Hitler fulminated soon after the war ended, "we demand - vengeance!" Germany's defeat, and the vindictive, misbegotten peace settlement that followed, irrevocably nurtured the seeds of Nazism, of an even more destructive war 20 years later, and of the Holocaust as well. The war of 1914-1918 was, as Simon Schama has put it, the "original sin" of the 20th century. Even the victors were losers: how could France, for example, be considered victorious when half of all Frenchmen aged 20 to 32 at the war's outbreak were dead when it was over?

Inaugurating industrialized slaughter on a scale previously unknown, the First World War remade the world for the worse in every conceivable way.

- - -

What kings, emperors, and prime ministers did not foresee, many others did. From 1914 on, tens of thousands of people in all the belligerent countries believed the war was not worth the horrendous cost in blood, and some anticipated with tragic clarity at least part of the nightmare that would engulf Europe as a result. Moreover, they spoke out at a time when to do so took great courage. In Germany, antiwar radicals like Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were sent to prison - as was the American socialist Eugene V. Debs after he left a sickbed to give a series of speeches when the United States entered the conflict. The judge told him he might get a lesser sentence if he repented. "Repent?" asked Debs. "Repent? Repent for standing like a man?" More than 500 American draft resisters went to prison.

Or consider a scene that unfolded a few weeks before that notorious first day on the Somme, not far away. In the spring of 1916, Britain had begun conscription, and some 50 men who were among the first to refuse it were forcibly inducted into the army and transported, some in handcuffs, across the English Channel to France. Family members and fellow pacifists were horrified. When questioned about the men, Lord Derby, director of military recruiting, declared that "if they disobey orders, of course they will be shot, and quite right too!"

- - -

It was in Britain that significant numbers of war resisters first acted on their beliefs and paid the price. They did not even come close to stopping the bloodshed, but their strength of conviction remains one of the glories of a dark time. By the conflict's end, more than 20,000 British men of military age would refuse the draft. Many, on principle, also refused the noncombatant alternative service offered to conscientious objectors, and more than 6,000 served prison terms under harsh conditions: hard labor, a bare-bones diet, and a strict "rule of silence." This was one of the largest groups ever jailed for political reasons in a Western democracy. War opponents behind bars also included older men - and a few women - as well. If we could time-travel our way into British prisons in late 1917 and early 1918 we would meet the nation's leading investigative journalist, a future winner of the Nobel Prize, more than half a dozen future members of Parliament, one future cabinet minister, and a former newspaper editor who was now publishing a clandestine journal for his fellow inmates on toilet paper.

- - -

When Rev. Edward Lyttelton, the headmaster of Eton, proposed some possible peace terms, the resulting uproar forced him to resign. From Parliament to pulpit, ferocity reigned. "Kill Germans! Kill them!" raged one clergyman in a 1915 sermon, "... not for the sake of killing, but to save the world... Kill the good as well as the bad... Kill the young men as well as the old... I look upon it as a war for purity. I look upon everybody who dies in it as a martyr." The speaker was Arthur Winnington-Ingram, the Anglican Bishop of London.

A West End theater put on a play mocking pacifists, called The Man Who Stayed At Home. Women stood on street corners handing out white feathers, an ancient symbol of cowardice, to young men not in uniform. Recruiting posters appealed to shame: one showed two children asking a frowning, guilty-looking father in civilian clothes, "Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?" (Bob Smillie, leader of the Scottish mineworkers, said his reply would be: "I tried to stop the bloody thing, my child.")

- - -

Part of [Bertrand] Russell's intellectual bravery lay in his willingness to confront that last set of conflicting loyalties. He described himself poignantly in the autumn of 1914 as being "tortured by patriotism... I desired the defeat of Germany as ardently as any retired colonel. Love of England is very nearly the strongest emotion I possess, and in appearing to set it aside at such a moment, I was making a very difficult renunciation." What left him even more anguished was realizing that "anticipation of carnage was delightful to something like ninety per cent of the population... As a lover of truth, the national propaganda of all the belligerent nations sickened me. As a lover of civilization, the return to barbarism appalled me. As a man of thwarted parental feeling, the massacre of the young wrung my heart." Over the four years to come, he never yielded in his belief that "this war is trivial, for all its vastness. No great principle is at stake, no great human purpose is involved on either side... The English and French say they are fighting in defence of democracy, but they do not wish their words to be heard in Petrograd or Calcutta."

Antiwar beliefs were tested most severely by the mass patriotic hysteria of the war's first months. "One by one, the people with whom one had been in the habit of agreeing politically went over to the side of the war." How hard it was, Russell wrote, to resist being swept away "when the whole nation is in a state of violent collective excitement. As much effort was required to avoid sharing this excitement as would have been needed to stand out against the extreme of hunger or sexual passion, and there was the same feeling of going against instinct." One night Russell heard a "shout of bestial triumph in the street. I leapt out of bed and saw a Zeppelin falling in flames. The thought of brave men dying in agony was what caused the triumph in the street."

By the beginning of 1916, in response to recruiting drives, posters ("Don't Lag! Follow Your Flag!"), and music-hall songs ("Oh, we don't want to lose you, but we think you ought to go"), 2.5 million volunteers had enlisted in the British military. But as battles on the Western Front devoured men by the hundreds of thousands, compounded by similarly bloody operations like the disastrous Gallipoli landing in Turkey, the army's appetite for bodies was such that Britain finally began a draft.

The authorities started raiding soccer games, movie theaters, and railway stations to round up military-age men who were not in uniform. A pamphlet by "A Little Mother" typically declared that "we women... will tolerate no such cry as 'Peace! Peace!'... There is only one temperature for the women of the British race, and that is white heat... We women pass on the human ammunition of 'only sons' to fill up the gaps." It sold 75,000 copies in a few days. "The conscientious objector is a fungus growth - a human toadstool - which should be uprooted without further delay," screamed the tabloid John Bull. In April 1916 the major group backing resisters, the No-Conscription Fellowship, or NCF, drew some 2,000 supporters to a London meeting hall while an angry crowd milled about in the street outside.

- - -

Not only soldiers perished in this war, for the conflict erased the traditional distinction between soldiers and civilians. Total war among industrialized economies meant that everybody was fair game, and each side tried to starve the other into submission. German U-boats torpedoed Allied and eventually neutral ships (which brought the United States into the war) carrying food and supplies to France and Britain. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy threw a tight blockade around Germany and its allies, sealing them off from all imports of food and fertilizer. Bad harvests in central Europe compounded the food shortages, and often the only meat on sale in Germany was that of dogs and cats. A foreign visitor described what happened when a horse collapsed and died on a Berlin street one morning: "Women rushed towards the cadaver as if they had been poised for this moment, knives in their hands. Everyone was shouting, fighting for the best pieces. Blood spattered their faces and their clothes... When nothing more was left of the horse beyond a bare skeleton, the people vanished, carefully guarding their pieces of bloody meat tight against their chests."

If there were ever a war that should have had an early, negotiated peace, it was this one. After all, before it began the major powers had been exchanging royal visits and getting along reasonably well. In public, at least, none of them claimed a piece of another's territory. Germany was Britain's biggest trading partner. But once the conflict was on, neither side was willing to consider anything but total victory. From the beginning, Bertrand Russell had ceaselessly proposed peace terms. He suggested that a future "International Council" resolve disputes before they turned into war. In 1916, he wrote to President Woodrow Wilson, urging him to use his influence to start peace talks, but with no result. Sometimes, however, encouragement came from unexpected sources. In December of that year, Russell received a letter that began, "Tonight here on the Somme I have just finished your Principles Of Social Reconstruction... It is only on account of such thoughts as yours, on account of the existence of men and women like yourself that it seems worth while surviving the war... You cannot mind knowing that you are understood and admired and that those exist who would be glad to work with you." The writer, 2nd Lieutenant Arthur Graeme West of the 6th Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, was killed by a sniper's bullet three months later, at the age of 25.

- - -

It was not only draft refusers who were locked up. In the spring of 1918, Russell himself was sentenced to six months for writings the authorities deemed subversive. When he arrived to begin serving his sentence, the warder taking down his particulars "asked my religion and I replied 'agnostic.' He asked how to spell it, and then remarked with a sigh: 'Well, there are many religions, but I suppose they all worship the same God.'"

- - -

After the bloodshed had continued without respite for three years, dissenters like these were joined by an unexpected voice that rang out from the very highest reaches of the country's hierarchy. Lord Lansdowne was a great landowner and former viceroy of India, minister for war, and foreign secretary. His doubts about battling to an unconditional victory began after the Somme. Very much a man of his class, he was particularly appalled by the number of British officers slain. "We are slowly but surely killing off the best of the male population of these islands..." he wrote. "Generations will have to come and go before the country recovers from the loss."

When the shocked London Times refused to publish it, an open letter from him appeared in the Daily Telegraph on November 29, 1917, laying out some proposals for a negotiated peace. "We are not going to lose this War," Lansdowne wrote, "but its prolongation will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it... Just as this war has been more dreadful than any war in history, so, we may be sure, would the next war be even more dreadful than this." Nearly three decades before Hiroshima, he prophetically sensed something about the future: "The prostitution of science for purposes of pure destruction is not likely to stop short." Lansdowne was attacked by many former colleagues, and in their confidential reports on the public mood, undercover intelligence agents began speaking darkly of "Lansdownism."

- - -

Bertrand Russell, who had recently completed his prison term, walked up Tottenham Court Road and watched Londoners pour out of shops and offices into the street to cheer. The public jubilation [because of armistice] made him think of the similar mood he had witnessed when war was declared more than four years earlier. "The crowd was frivolous still, and had learned nothing during the period of horror... I felt strangely solitary amid the rejoicings, like a ghost dropped by accident from some other planet."

Fonte:

http://theamericanscholar.org/i-tried-to-stop-the-bloody-thing

FOLHA DE SÃO PAULO

1 de março de 2013

Gabriele d'Annunzio: poeta, sedutor e apóstolo da guerra

O homem que Mussolini definiu como o "João Batista" do fascismo foi um herói nacional com apetite insaciável por sexo.

(Thomas Jones)

Em 7 de agosto de 1915, Gabrielle d'Annunzio e Giuseppe Miraglia decolaram de Veneza em um avião, rumo a Trieste, então ainda parte do Império Austro-Húngaro, com uma carga de bombas e panfletos de propaganda. Miraglia, o piloto, tinha 32 anos e era oficial do exército italiano; d'Annunzio, que voava no assento do observador, era 20 anos mais velho que o companheiro e famoso em toda a Itália, Europa e mais além, como escritor, libertino e nacionalista feroz. Ele carregava um caderno, no qual anotou suas impressões sobre Veneza vista do ar ("os tortuosos canais, verdes como malaquita"), e usava as páginas para escrever mensagens a Miraglia: "Você quer um café?"

Ao chegar a Trieste, eles foram alvo de fogo inimigo. Miraglia mergulhou com o avião por sobre a marina da cidade, e d'Annunzio lançou bombas contra os submarinos austríacos e folhetos (cujo texto ele mesmo havia escrito) nas piazzas. Quando tomaram o curso de retorno à Itália, perceberam que uma das bombas havia ficado presa ao avião. "Veja se você consegue empurrá-la", Miraglia escreveu no caderno de d'Annunzio. "Mas não a gire". O escritor deve ter conseguido realizar a manobra, porque o avião pousou em segurança em Veneza. D'Annunzio havia acabado de "iniciar sua nova vida como herói nacional", escreve Lucy Hughes-Hallett em "The Pike: Gabriele d'Annunzio - Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War", a nova e instigante biografia desse "poeta, sedutor e apóstolo da guerra".

- - -

Uma das melhores descrições sobre a voz hipnótica de d'Annunzio vem da filha adolescente do compositor Pietro Mascagni: "Quando o signor d'Annunzio fala, é sempre como se estivesse contando um segredo ao interlocutor. Mesmo que esteja apenas dizendo bom dia". Ela o conheceu em Paris, para onde o escritor se mudou em 1910 a fim de escapar aos seus credores na Itália.

D'Annunzio fez um retorno triunfal ao seu país em maio de 1915, convidado a discursar na inauguração de um monumento a Garibaldi em Quarto, perto de Gênova. Ele usou sua voz mágica para falar às vastas multidões que acorreram para recebê-lo -100 mil pessoas quando ele chegou a Roma, em 12 de maio, de acordo com o jornal "Corriere della Sera" -, apelando para que a Itália entrasse na guerra e completasse a unificação do país pela anexação de vastas porções do Império Austro-Húngaro - ainda que a decisão de fazê-lo já tivesse sido tomada de modo irrevogável quando o escritor ainda estava na França.

O imenso morticínio e os três anos de impasse na campanha dos montes Dolomitas em nada reduziram o entusiasmo de d'Annunzio pela guerra. Ele perdeu muitos amigos, entre os quais Miraglia, e ficou cego de um olho depois da queda de um avião em que estava voando. Mas depois do armistício escreveu que "sinto o fedor da paz". Para d'Annunzio, a guerra não estava acabada: em setembro de 1919, ele liderou um pequeno exército de combatentes irregulares e soldados amotinados e ocupou a cidade de Fiume (hoje Rijeka, na Croácia), cujo controle estava em disputa, estabelecendo-se como ditador. Reinou por 15 meses como "Duce" de Fiume, até que um bombardeio da marinha italiana o forçou a se retirar.

Em fevereiro de 1921 ele se mudou para a casa vizinha ao lago Garda onde viveria em reclusão parcial até a morte, em 1938, dedicando-se à cocaína, coito e decoração de interiores. Sua aposentadoria foi bancada, majoritariamente, pelo governo fascista, que queria mantê-lo quieto e fora do caminho. Mussolini desejava promover d'Annunzio como o João Batista do fascismo, e fazê-lo seria muito mais fácil caso o homem, que discordava dessa interpretação, estivesse fora do caminho.

"Ainda que d'Annunzio não fosse fascista", afirma Hughes-Hallet, "o fascismo era d'annunziano". Em 1892, ele havia escrito que "os homens serão divididos em duas raças. Aos superiores, que se terão erguido pela pura energia de sua vontade, tudo será permitido; aos inferiores, nada ou quase nada".

Fonte:

http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/1238676-gabriele-dannunzio-poeta-sedutor-e-apostolo-da-guerra.shtml

Mais:

http://docs.google.com/file/d/1vDKxmGtlHbWk-U4w6jYX7slJje39E-L2

A quantidade de material (não só sobre a WW1) disponível no site Old Magazine Articles é no mínimo desnorteante.

The First World War had only been raging for six months when this article first appeared in a 1915 issue of THE NEW REPUBLIC. As the journalist makes clear, one did not have to have an advanced degree in history to recognize that this war was unique; it involved almost every wealthy, industrialized European nation and their far-flung colonies; thousands of men were killed daily and many more thousands stepped forward to take their places. The writer recognized that this long anticipated war was an epic event and that, like the French Revolution, it would be seen by future generations as a marker which indicated that all changes began at that point.

THE NEW REPUBLIC

January 2, 1915

1914 - The end of an era?

(Frank H. Simonds)

In its immediate effects upon the lives and fortunes of millions of men and women, the great war is unmistakably the largest human fact since the French Revolution. Since that tremendous deluge overflowed the frontiers of the Old Monarchy and began its resistless march from Paris to Moscow, from the Straits of Dover to the Syrian Coast, there has been no single disturbance of the whole system of nations and continents comparable with that which is now going on before our eyes.

Yet in the face of this almost limitless destruction there is patent on many sides a disposition to regard it as an accident, a piece of collective insanity on the part of races and nations certain to be followed presently by a sad return to sanity. Those who were but a few months ago assuring us that there never could be another general war are most vociferously informing the same audience that this will be the last. In the same sense there is the general tendency to assert that when it has come to an end we shall be as we were before, that after a temporary if terrible interruption nations and continents will return to the same tasks, the same ideas, the same ideals which they followed up to the fatal first of August, 1914.

Going back to the French revolution, is it not quite as clear from any reading of contemporary comment that a similar expectation prevailed everywhere save in Paris when the Allies at last undertook the little "police expedition" into France which was to bring the French people to their senses, restore a Bourbon to the throne, an aristocracy to control? Was it not quite as inevitable in the minds of those who directed the first invasion of France, which terminated at Valmy, that in a brief time the world was to be exactly as it had been before 1789, as it is now to many minds, that the treaty of peace which closes the present chapter will send the world back to the precise point from which it started on this temporary explosion of madness?

Accepting this as possible, is it inevitable? Is it not a possibility that what is taking place marks quite as complete a bankruptcy of ideas, systems, society, as did the French Revolution? For Carlyle, in many ways the most satisfactory interpreter of the French Revolution, it was above all else a conflagration, a burning up of shams, of inveracities, a forest fire sweeping through woods long dead and become tinder, a total dissolution of a world which had become unreal, inveracious, devitalized.

Now it is at least plain that the very fact of a world war is a negation of all that the contemporary generation has believed, has accepted, has asserted. As a final evidence of the stability of the order existing before the war, we have been accustomed to point to at least four bulwarks, each a product of contemporary genius, each a prop and promise of the perpetuation of what was frankly conceded to be the best and the wisest social order ever devised by the mind of man. These four forces may be described as science, sentiment, high finance and socialism.

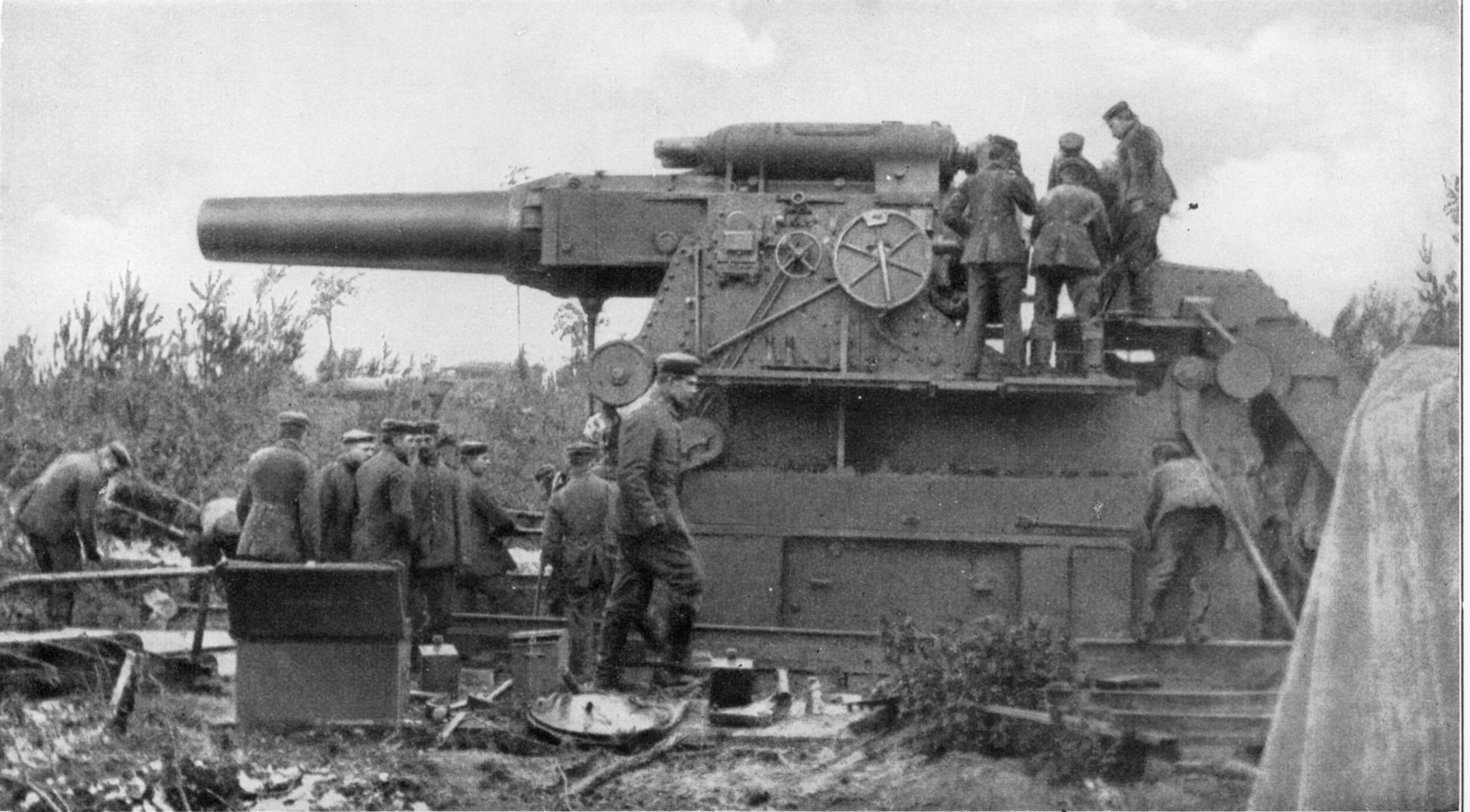

As to science, it will be remembered that twenty years ago M. Bloch quite convinced a willing world that war had become impossible because modern weapons had made the cost of battle beyond the resource of men or nations to pay. In that time the world eagerly read carefully prepared tables which showed that, given the power of modern artillery and rifle, battles would now be more terrible than any known to history. From this fact it was reasoned that men would not fight, nations would not dare to send their citizens to battle. Yet after twenty years it was fully demonstrated in the Balkan War that all the terrible destructiveness of modern weapons did not prevent men from fighting, and from fighting hand to hand. It was the bayonet and not the artillery which decided Monastir and Kirk Killisse. The Bulgarian "Na noge" was still the watchword of battle, and the knife terrible in European warfare as in African. Today each report of battle brings the details of bayonet charges comparable with those that made Gettysburg famous and Waterloo immortal. Thus science, which in twenty years has added much to the terrors foreseen by M. Bloch, has given us the 42-centimetre gun and the French "75" has in no degree weakened the spirit of man. As the Greeks, the Romans, the fighting races of all past time fought, so the great nations of twentieth century Europe are fighting. Science has made war more terrible, more costly, but it has not made war impossible, filled man with controlling terror. Thus it has failed.

Is it less plain that sentiment, the sentiment that was behind The Hague Conferences, the international arrangements, the endless "scrap of paper" and agreements, the indefinable thing we call humanitarian spirit, has failed quite as completely? It did not avail to prevent the invasion of Belgium, the laying in waste of East Prussia. Has there been any time since the Thirty Years' War when the map of Europe could show so many regions devasted, so many millions homeless, destitute? Has war ever been more horrible in its manifestations than this time, when the ashes of Louvain, the ruins of Belgium, Polish, Galician, French, and Prussian towns lie before a world? Has war ever been more dreadful than now, when we count in Germany alone not less than 1,500,000 men killed and wounded in five months? Yet in any nation at war is there any present agitation for peace?

High finance failed in the last week of July. Everyone remembers how, in the last days before shooting began, there was of a sudden a flurry in all the world of finance, a sudden report that at last the men who were the masters of millions had served their ultimatum on statesmen, threatened, commanded, bullied. That little interruption had its climax on July thirty-first. But on August first Germany declared war on Russia, and before the following week was over, the battle lines stretched straight across the Continent. There never was anything more complete, more decisive than the defeat of world finance when it undertook to take the helm in storm.

Last of all there was socialism. Ten years ago it was the fashion to believe that socialism, with its annex of internationalism, had quite permeated and conquered Europe. French and German workmen, faced by battle, were to ground their arms and fraternize. Bebel and Jaurès were to succeed Bismarck and William II. All France was in the hands of the socialists, the flag was on the dunghill, and the army was in disgrace. Pelletan was telling Frenchmen that a navy was of use merely as a school. Jaurès was describing an armed citizenry as the outside limit of legitimate self-defense, ideas strangely familiar to American ears just now.

Yet when the war came, instead of fraternization a Frenchman shot Jaurès; a socialist became the greatest French War Minister since the elder Carnot; Jules Guesde entered the ministry in France, Vandervelde in Belgium. The workmen of Moscow, on a strike which was mounting rapidly toward rebellion, voluntarily went back to work. The socialists in the Reichstag voted the war funds, and French socialists went to the battle line frankly affirming their desire to atone with their lives for their share in disarming France.

In sum, socialism, like all the other props, broke down instantly, and today no socialist ventures to say with assurance whether the end of the war will leave socialism a forgotten thing or place it on the seat of power; but all socialists recognize that the temper and the spirit of the men who are now fighting a great struggle holds out little present promise of any return to old pathways and ante-bellum ideals.

It is wholly possible that when at last peace comes, it will be proven that this war was the great accident most men now bold it, an illogical and unrelated interruption of the course of human ideas and ideals, all correctly established and asserted before 1914. But is it not quite as possible that a whole new order of ideas, ideals, perhaps a religious awakening, probably a new outburst of national spirit and patriotism in all races, may come? "All the king's horses and all the king's men" could not set the old order up again after the French Revolution; may it not be as impossible after this great war? May not 1914, like 1789, mark in human history the end of an era?

Fonte:

http://oldmagazinearticles.com/Why_was_1914_the-End_of_an_Era

RADIOLOGY AT THE FRONT

Three German bombs fell on Paris on September 2, 1914, about a month after Germany declared war on France. By that time construction of the Radium Institute was complete, although Curie had not yet moved her lab there. Curie's researchers had been drafted, like all other able-bodied Frenchmen.

The Radium Institute's work would have to wait for peacetime. But surely there were ways in which Curie could use her scientific knowledge to advance the war effort.

As the German army swept toward Paris, the government decided to move to Bordeaux. France's entire stock of radium for research was the single gram in Curie's lab. At the government's behest, Curie took a Bordeaux-bound train along with government staff, carrying the precious element in a heavy lead box. Unlike many, however, Curie felt her place was in Paris. After the radium was in a Bordeaux safe-deposit box, she returned to Paris on a military train.

X-rays could save soldiers' lives, she realized, by helping doctors see bullets, shrapnel, and broken bones. She convinced the government to empower her to set up France's first military radiology centers. Newly named Director of the Red Cross Radiology Service, she wheedled money and cars out of wealthy acquaintances.

She convinced automobile body shops to transform the cars into vans, and begged manufacturers to do their part for their country by donating equipment. By late October 1914, the first of 20 radiology vehicles she would equip was ready. French enlisted men would soon dub these mobile radiology installations, which transported X-ray apparatus to the wounded at the battle front, petites Curies (little Curies).

Although Curie had lectured about X-rays at the Sorbonne, she had no personal experience working with them. Intending to operate the petite Curie herself if necessary, she learned how to drive a car and gave herself cram courses in anatomy, in the use of X-ray equipment, and in auto mechanics. As her first radiological assistant she chose her daughter Irène, a very mature and scientifically well-versed 17-year-old. Accompanied by a military doctor, mother and daughter made their first trip to the battle front in the autumn of 1914.

Would Irène be traumatized by the sight of the soldiers' horrific wounds? To guard against a bad reaction, Curie was careful to display no emotion herself as she carefully recorded data about each patient.

Irène followed her mother's example. Heedless of the dangers of over-exposure to X-rays, mother and daughter were inadequately shielded from the radiation that helped save countless soldiers' lives. After the war the French government recognized Irène's hospital work by awarding her a military medal. No such official recognition came to Curie. Perhaps her role in the Langevin affair was not yet forgiven.

A MILITARY RADIOTERAPHY SERVICE

Curie knew she needed more trained personnel. She and Irène could not run by themselves the 20 mobile X-ray stations she had established, nor the 200 stationary units. By 1916 Marie began to train women as radiological assistants by offering courses in the necessary techniques at the Radium Institute. She was assisted by Irène, who was also enrolled as a student at the Sorbonne.

Her radiological services well under way, Curie turned her attention to establishing a military radiotherapy service. By 1915 it seemed likely that the Germans could not take Paris. After retrieving the gram of radium from Bordeaux, Curie began to use a technique pioneered in Dublin to collect radon - a radioactive gas that radium steadily emits. Working alone, without protecting herself adequately from the radioactive vapors, she used an electric pump to collect the gas at 48-hour intervals. She sealed the radon in thin glass tubes about one centimeter long, which were delivered to military and civilian hospitals. There doctors encased the tubes in platinum needles and positioned them directly within patients' bodies, in the exact spot where the radiation would most effectively destroy diseased tissue.

Should she hand over her medals to the government? In addition to the contributions to the war effort that Curie could make as a scientist, she was also an ordinary citizen. When the government asked people to contribute their gold and silver, Curie decided to offer her two Nobel medals, along with all the other medals bestowed on her over the years. The French National Bank turned down the offer, but Curie did her part by using most of the Nobel prize money to buy war bonds.

The war ended on November 11, 1918, but Curie's war-related work continued for nearly another whole year. During the spring of 1919 she offered radiology courses to a group of American soldiers who remained in France while awaiting passage home. That summer she summarized much of her wartime work in a book titled Radiology in War. By the fall of 1919 her laboratory at the Radium Institute was finally ready. She would devote most of the rest of her life to it.

Fonte:

http://www.aip.org/history/curie/war1.htm

Mais:

http://www.lefigaro.fr/histoire/marie-curie-la-radiologie-et-la-grande-guerre-1914.php

http://docs.google.com/file/d/0BxwrrqPyqsnIUThzVTc3NS1UcWc