Extraordinário o trabalho realizado por J. Fred MacDonald no site em que ele reúne artigos sobre a 1ª Guerra.

[The noted Russian author wrote this pithy little article for a Stockholm paper in March 1916. It was copied by a Russian journal, from which the present translation was made.]

War and Civilization

(Maxim Gorky)

The effect of the war on the progress of civilization among the nations of the world will be strongly felt for generations to come. The development of civilization will be much less rapid after the war than heretofore. The world is becoming more and more permeated with ill-will, hatred, and passion. The noble emotions give way to the bestial. The infernal forces are awakened and the inhuman has pridefully raised its head.

I believe, however, in the common sense of the nations of Western Europe. I feel that that sense will yet conquer the world, and that the European civilization will become the civilization of all humanity.

The European nations must therefore see to it that the work of civilization is carried on by them in a friendlier and more co-operative spirit. The "must" is based on a very plain point of view: The Anglo-Saxons, Teutons and Latins, all together, constitute but a part of the world's population.

And yet they are the ones that are and have been creating the spiritual treasures of all humanity. The right to the spiritual domination of the world belongs to Western Europe, as she is entitled to that right by virtue of her spiritual wealth, of her many generations of labor on the fields of science and art; she has won that right through her intellectual services to humanity.

This mad, bloody war affords the largest part of the world the opportunity of doubting the moral values of Western European progress, of denouncing her authority in matters spiritual, and of opposing her doctrines and principles. In a measure these doubts are justified. The slaughter in which the foremost European nations are now engaged will enhance barbarism on earth and will doubtless be the cause of many obstacles in the path of civilization's progress in Africa and Asia.

As soon as the European nations end their present criminal activities, a safe and solid ground for common work in behalf of the world will be found by them. The great minds of the neutral countries could even now begin the work of reorganizing European civilization, they could start a campaign against a return to barbarism.

Several years ago Wilhelm Ostwald suggested a union of the great minds of the world. He pointed out the necessity for such a "world-brain," representing all nations. Such a "world-brain" would bring into the political, social, and nationalistic chaos the healthy human thought. Ostwald has proved the possibility of creating such a scientific institution in international politics, an institution composed of the master minds of the age, of scholars and men of affairs. Such a union must become the nervous system of humanity, the brain of the world.

I believe that right now is the time for such a union. We must attempt to embody this idea even if it were only because it would raise us above the every-day struggle for life, ennoble and refine us.

Does it sound Utopian? Not so very long ago the people thought wireless telegraphy, flying machines, and many other facts of today Utopian. The properties of radium remind us of the "philosopher's stone," the dream of the alchemists. Are not all these the attainments of science?

These miracles of science are the products of the human mind, the results of the iron will of man. Why could not the same mind, the same will, work miracles on the field of social and nationalistic relations?

Would it be considered miraculous if all of us were to grasp fully the simple fact that through bloodshed, murder, and destruction our conditions of life will not improve?

It is high time for our mind and will to create the possibilities for a healthier, freer, and more rapid development of civilization. Only through the power of mind and will could man transform the earth into a place worthy of his aspirations and ideals. Only a rational will could create rational conditions of life. And now, when the war has caused us all so much suffering, let our common interests in the destinies of European civilization create a mutual spiritual bond, a union based on our devotion to civilization.

Fonte:

http://www.jfredmacdonald.com/worldwarone1914-1918/perspectives-16war-civilization.html

Mais:

http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrWPsj6fVbeUIs0U-2ANgWtznZ56p8iF3

http://en.ria.ru/forgotten_war

Guerra e Paz

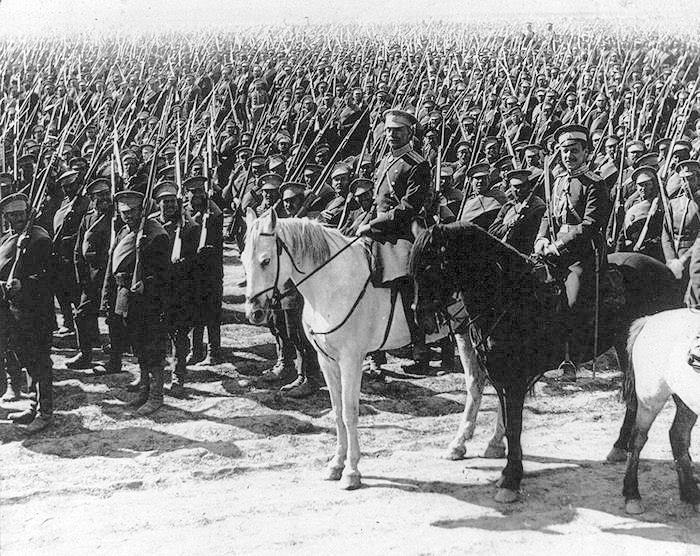

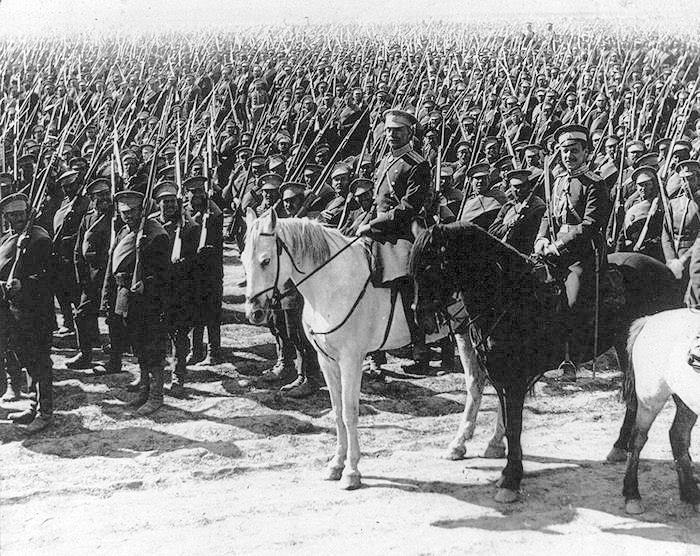

Russian troops invade East Prussia

On this day [August 17] in 1914, the Russian 1st and 2nd Armies begin their advance into East Prussia, fulfilling Russia's promise to its ally, France, to attack Germany from the east as soon as possible so as to divert German resources and relieve pressure on France during the opening weeks of the First World War.

The Russian 1st Army, commanded by Pavel Rennenkampf, and the 2nd Army, led by Aleksandr Samsonov, advanced in a two-pronged formation - separated by the Masurian Lakes, which stretched over 100 kilometers - aiming to eventually meet and pin the German 8th Army between them. For the Germans, the Russian advance came much sooner than expected; counting on Russia's slow preparation in the east, they had sent the great bulk of their forces west to face France. By August 19, Rennenkampf's 1st Army had advanced to Gumbinnen, where they faced the German 8th Army - commanded by General Maximilian von Prittwitz - in battle on the River Angerapp on August 20.

During the Battle of Gumbinnen, Prittwitz received an aerial reconnaissance report that Samsonov's 2nd Russian Army had advanced to threaten the region and its capital city, Konigsberg (present-day Kaliningrad) as well. With his forces greatly outnumbered in the region, he panicked, ordering the 8th Army to fall back to the Vistula River, against the advice of his staff and against the previous orders of the chief of the German general staff, Helmuth von Moltke, who had told him "When the Russians come, not defense only, but offensive, offensive, offensive." From his headquarters at Koblenz, Moltke consulted with Prittwitz's corps commanders and subsequently dismissed the general, replacing him with Paul von Hindenburg, a 67-year-old retired general of great stature. As Hindenburg's chief of staff, he named Erich Ludendorff, the newly anointed hero of the capture of Belgium's fortress city of Liege earlier that month.

Under this new leadership, and awaiting reinforcements summoned by Moltke from the Western Front, the German 8th Army prepared to face off against the Russians in East Prussia. Meanwhile, confusion reigned on the other side of the line, as the two advancing armies and their commanders, Rennenkampf and Samsonov, were cut off from each other and unable to successfully coordinate their attacks, despite enjoying numerical superiority over the Germans. This lack of communication would prove costly in the last week of August, when the Germans enveloped and devastated Samsonov's 2nd Army, scoring what would be their greatest victory of the war on the Eastern Front in the Battle of Tannenberg. The battle elevated Hindenburg and Ludendorff to the status of national heroes in Germany. Their partnership, born in East Prussia in the opening weeks of the war, would eventually acquire mythic status, as the two men moved forward together at the heart of the German war effort, right up to the bitter end in 1918.

Fonte:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/russian-troops-invade-east-prussia

Mais:

http://russianhistoryblog.org/2011/02/atrocities-in-east-prussia-1914

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JidDI60nBqw

|

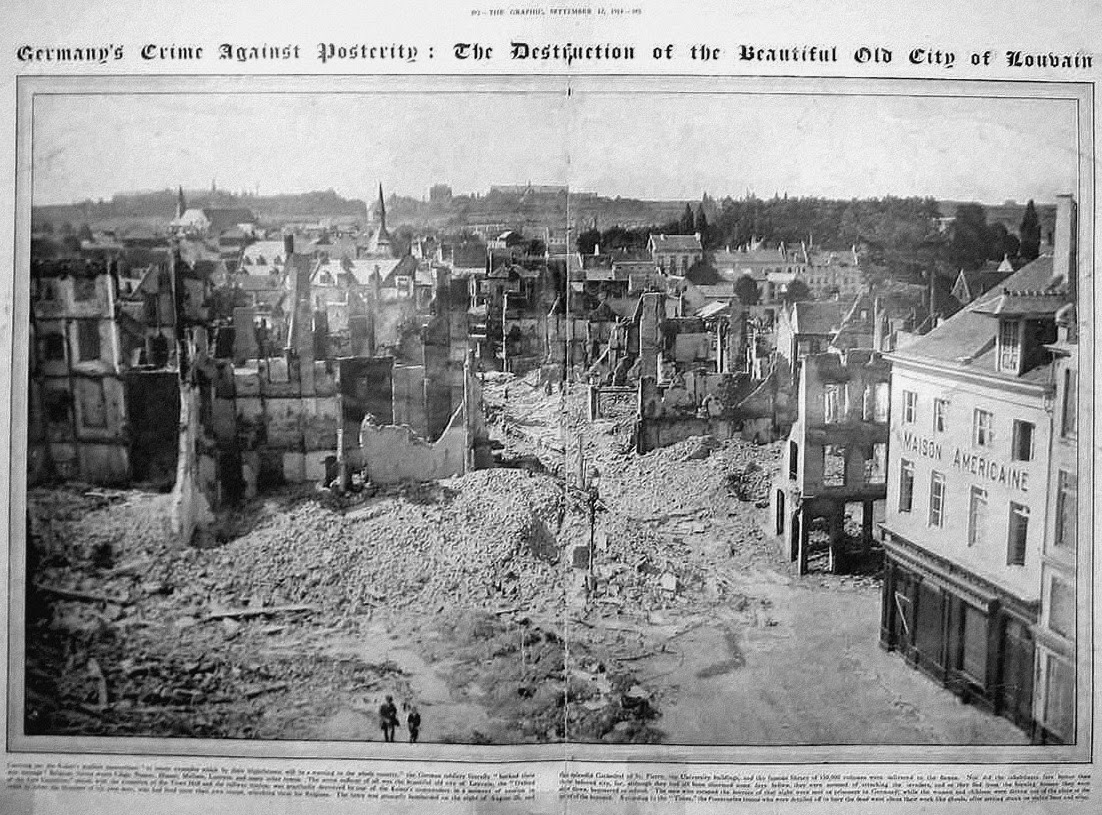

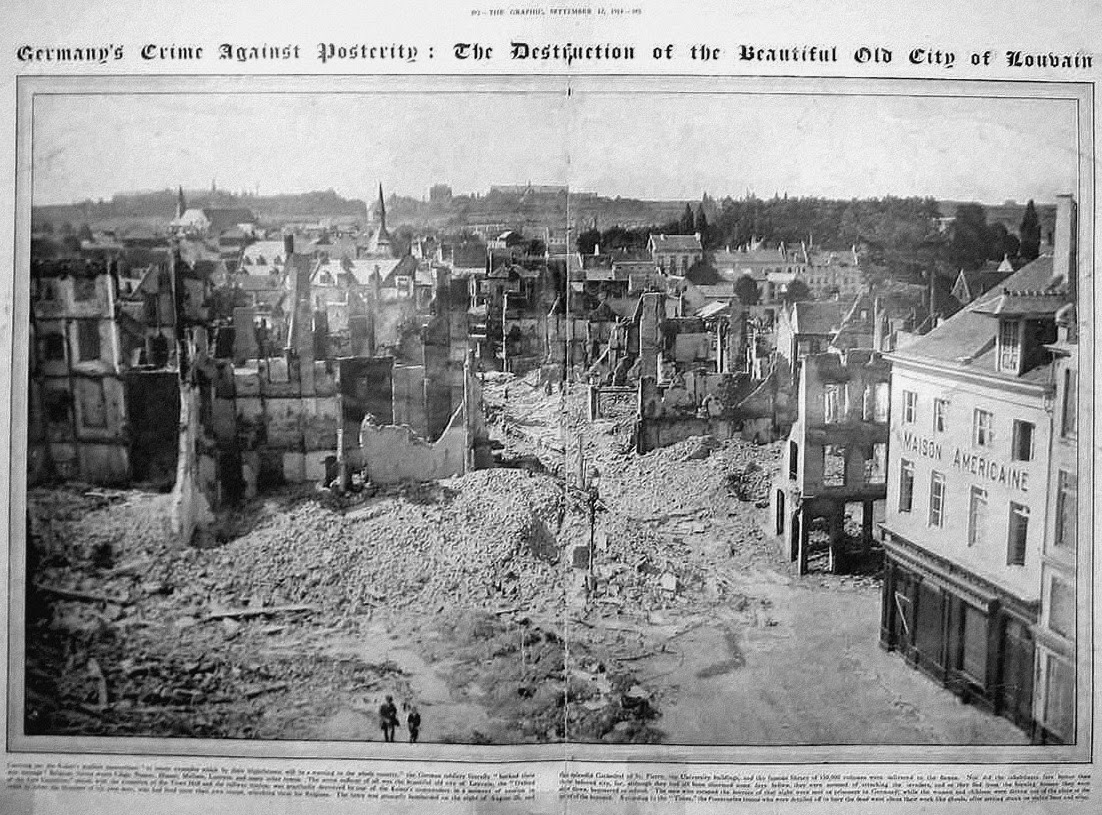

Germans burn Belgian town of Louvain

Over the course of five days, beginning August 25, 1914, German troops stationed in the Belgian village of Louvain during the opening month of World War I burn and loot much of the town, executing hundreds of civilians.

Located between Liege, the fortress town that saw heavy fighting during the first weeks of the German invasion, and the Belgian capital of Brussels, Louvain became the symbol, in the eyes of international public opinion, of the shockingly brutal nature of the German war machine. From the first days they crossed into Belgium, violating that small country's neutrality on the way to invade France, German forces looted and destroyed much of the countryside and villages in their path, killing significant numbers of civilians, including women and children. These brutal actions, the Germans claimed, were in response to what they saw as an illegal civilian resistance to the German occupation, organized and promoted by the Belgian government and other community leaders - especially the Catholic Church - and carried out by irregular combatants or franc-tireurs (snipers, or free shooters) of the type that had participated in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71.

In reality this type of civilian resistance - despite being sanctioned by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which the Germans objected to - did not exist to any significant degree in Belgium during the German invasion, but was used as an excuse to justify the German pursuit of a theory of terror previously articulated by the enormously influential 19th-century Prussian military philosopher Karl von Clausewitz. According to Clausewitz, the civilian population of an enemy country should not be exempted from war, but in fact should be made to feel its effects, and be forced to put pressure on their government to surrender.

The burning of Louvain came on the heels of a massacre in the village of Dinant, near Liege, on August 23, in which the German soldiers had killed some 674 civilians on the orders of their corps commander. Two days later, the small but hardy Belgian army made a sudden sharp attack on the rear lines of the German 1st Army, commanded by General Alexander von Kluck, forcing the Germans to retreat in disorder to Louvain. In the confusion that followed, they would later claim, civilians had fired on the German soldiers or had fired from the village's rooftops to send a signal to the Belgian army, or even to approaching French or British troops. The Belgians, by contrast, would claim the Germans had mistakenly fired on each other in the dark. Whatever happened did not matter: the Germans burned Louvain not to punish specific Belgian acts but to provide an example, before the world, of what happened to those who resisted mighty Germany.

Over the next five days, as Louvain and its buildings - including its renowned university and library, founded in 1426 - burned, a great outcry grew in the international community, with refugees pouring out of the village and eyewitness accounts filling the foreign press. Richard Harding Davis, an American correspondent in Belgium, arrived at Louvain by troop train on August 27; his report later appeared in the New York Tribune under the headline GERMANS SACK LOUVAIN; WOMEN AND CLERGY SHOT. A wireless statement from Berlin issued by the German Embassy in Washington, D.C., confirmed the incidents, stating that "Louvain was punished by the destruction of the city." The Allied press went crazy, with British editorials proclaiming "Treason to Civilization" and insisting the Germans had proved themselves descendants not of the great author Goethe but of the bloodthirsty Attila the Hun.

By war's end, the Germans would kill some 5,521 civilians in Belgium (and 896 in France). Above all, German actions in Belgium were intended to demonstrate to the Allies that the German empire was a formidable power that should be submitted to, and that those resisting that power - whether soldier or civilian, belligerent or neutral - would be met with a force of total destruction. Ironically, for many in the Allied countries, and in the rest of the world as well, a different conclusion emerged from the flames of Louvain: Germany must be defeated at all costs, without compromise or settlement, because a German victory would mean the defeat of civilization.

Fonte:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-burn-belgian-town-of-louvain

Mais:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ok1nKxeXJg

http://docs.google.com/file/d/1yXck-3LJcul-ZEw2kUBQnFRPKxgrvUfE

Um mês após a dura Batalha de Mons, na 1ª Guerra Mundial, foi publicada no Evening News, de Londres, uma notícia que causou sensação na época e provocou uma controvérsia que ainda dura.

A notícia, assinada por um jornalista e escritor galês, Arthur Machen, referia como uma pequena força expedicionária britânica, numa desproporção numérica de 3 para 1 em relação ao inimigo, fora salva por reforços celestiais. Os Anjos de Mons (ou O Anjo; os relatos variam entre um e outro pelotão) surgiram repentinamente entre os ingleses e os alemães, que se defrontavam numa batalha. Compreensivelmente, estes últimos recuaram em grande confusão.

A batalha travou-se no dia 26 de Agosto de 1914, e quando a notícia foi publicada, em setembro seguinte, a maioria dos sobreviventes encontrava-se ainda na França. No mês de maio do ano seguinte, a filha de um pastor de Clifton, na cidade de Bristol, publicou anonimamente, na revista da paróquia, o que afirmou ser a declaração, prestada sob juramento, de um oficial britânico.

Nela o oficial declarava que, quando sua companhia se retirava de Mons, fora perseguida por uma unidade de cavalaria alemã. O oficial tentara alcançar um local onde a companhia pudesse abrigar-se e combater, mas os alemães haviam-nos precedido.

Esperando uma morte quase certa, os ingleses voltaram-se e viram então, para seu espanto, uma companhia de anjos entre eles e o inimigo. Os cavalos alemães, aterrorizados, fugiram desordenadamente em todas as direções.

Um capelão do Exército, o Reverendo C. M. Chavasse, irmão de Noel Chavasse, condecorado com a Victoria Cross e mais tarde Bispo de Rochester, declarou ter ouvido relatos semelhantes de um brigadeiro e dois de seus oficiais.

Um tenente-coronel descreveu como, aquando da retirada, o seu batalhão fora escoltado durante 20 minutos por uma cavalaria fantasma.

Do lado alemão surgiu a notícia de que os combatentes germânicos recusaram-se a atacar em um determinado ponto onde as linhas inglesas tinham sido cortadas, devido à presença de grande quantidade de tropas. Segundo os registros dos Aliados, não havia nessa altura um único soldado inglês na área.

UM ESCRITOR COM IMAGINAÇÃO

Um pormenor notável no que respeita a todos os relatos sobre Mons é que nenhum deles foi divulgado a primeira mão. Em todos os casos, os oficiais que transmitiram a notícia quiseram ficar no anonimato, temendo que o seu relato não fosse considerado digno de crédito e que tal fato constituísse um obstáculo a uma possível promoção.

Anos depois, Machen, autor de histórias de terror e do sobrenatural, que fora membro da sociedade mística conhecida pelo nome de Ordem Hermética da Aurora Dourada, reconheceu que a primeira notícia que divulgara não passava de imaginação.

O mistério tornou-se assim mais intrigante ainda. Apesar do desmentido, muitos soldados de regresso à pátria entregaram-se a reminiscências sobre os estranhos acontecimentos de Mons, e os investigadores chegaram a acreditar que, de fato, algo sobrenatural ocorrera.

Teriam os soldados regressados da guerra recorrido a uma história que lhes agradava e que apoiavam determinadamente? Ou teria acontecido algo - uma miragem, por exemplo - que induzira os ingleses e os alemães a acreditarem que haviam visto um exército espectral de anjos?

Qualquer que seja a explicação, os ingleses conseguiram algo semelhante a um milagre. Apesar de uma desvantagem esmagadora e de pesadas perdas, a retirada foi realizada com êxito, e a Força Expedicionária Britânica manteve-se uma efetiva força de combate.

Fonte:

http://sobrenatural.org/conto/detalhar/13928/anjos_de_mons_

Mais:

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/14044/pg14044.html

Trechos de Viagem Ao Fim Da Noite (1932), de Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Esses alemães agachados na estrada, teimosos e atiradores, atiravam mal, mas pareciam ter balas para dar e vender, sem dúvida depósitos abarrotados. A guerra positivamente não havia terminado! Nosso coronel, a gente tem que dizer as coisas como elas são, demonstrava uma bravura assombrosa! Passeava em plena estrada, e depois para lá e para cá entre a trajetória das balas, com tanta tranquilidade como se estivesse esperando um amigo na plataforma de uma estação de trem, só que um pouco impaciente.

Esses alemães agachados na estrada, teimosos e atiradores, atiravam mal, mas pareciam ter balas para dar e vender, sem dúvida depósitos abarrotados. A guerra positivamente não havia terminado! Nosso coronel, a gente tem que dizer as coisas como elas são, demonstrava uma bravura assombrosa! Passeava em plena estrada, e depois para lá e para cá entre a trajetória das balas, com tanta tranquilidade como se estivesse esperando um amigo na plataforma de uma estação de trem, só que um pouco impaciente.

Eu primeiro o campo, é bom ir logo dizendo, nunca o suportei, sempre o achei triste, com seus atoleiros intermináveis, suas casas onde as pessoas nunca estão e seus caminhos que não levam a lugar algum. Mas quando ainda por cima a ele se soma a guerra, então é mesmo de amargar.

- - -

Seria eu portanto o único covarde nesta terra? pensava. E com que pavor!... Perdido entre dois milhões de doidos heroicos e enfurecidos e armados até a raiz dos cabelos? Com capacetes, sem capacetes, sem cavalos, em cima de motocicletas, berrando, de automóvel, apitando, atiradores, conspiradores, volantes, ajoelhados, cavando, se esquivando, caracolando pelas picadas, estrondeando, escondidos debaixo da terra, como numa choupana, para tudo destruir, Alemanha, França e Continentes, tudo que respira, destruir, mais raivosos que os cães, adorando essa raiva.

- - -

Logo depois, pensei no segundo-sargento Barousse que acabava de explodir, conforme o outro nos informara. Era uma boa notícia. Antes isso!, foi o que imaginei na mesma hora, assim: "É um canalha de menos no regimento!". Ele quis que eu fosse julgado pelo Conselho por causa de uma lata de conserva. "Cada um com sua guerra!", pensei com meus botões. Quanto a isso, é preciso reconhecer, de vez em quando ela servia para alguma coisa, a guerra! Eu bem que ainda conhecia mais três ou quatro no regimento, uns pulhas desgraçados, a quem eu ajudaria de bom grado a encontrar um obus, igual ao Barousse.

Quanto ao coronel, eu não lhe queria mal. No entanto, ele também tinha morrido. Primeiro, não o vi mais. É que fora deportado para cima do talude, deitado de banda por causa da explosão e projetado nos braços do cavaleiro a pé, o mensageiro, igualmente liquidado. Os dois se beijavam, naquele momento e para sempre, mas o cavaleiro não tinha mais cabeça, só uma abertura em cima do pescoço, com sangue dentro que cozinhava em fogo brando fazendo gluglu como geleia no tacho. O coronel estava com a barriga aberta e fazia uma careta horrorosa. Deve ter lhe doído à beça, aquele negócio, na hora em que aconteceu. Azar o dele! Se tivesse ido embora desde as primeiras balas, isso não lhe teria acontecido.

- - -

O entusiasmo do capitão Ortolan, mesmo entre tantos outros estoura-vergas, ia se tornando cada dia mais notável. Ele cheirava cocaína, é o que também se contava. Pálido e com olheiras, sempre agitado em cima de seus membros frágeis, quando botava o pé no chão primeiro cambaleava e depois se reaprumava e calcorreava furiosamente para lá e para cá em busca de um feito de bravura. Teria nos mandado apanhar fogo na boca dos canhões do inimigo.

- - -

Nada restava na aldeia, de vivo, a não ser gatos apavorados. As mobílias bem quebradas primeiro passavam a servir de lenha para a cantina, cadeiras, poltronas, bufês, do mais leve ao mais pesado. E tudo quanto podiam pôr nas costas, eles levavam consigo, meus companheiros. Pentes, pequenos abajures, xícaras, cacarecos inúteis, até grinaldas de noivas, tudo prestava. Como se ainda tivessem anos e anos de vida. Roubavam para se distrair, para dar a impressão de que ainda tinham muito tempo pela frente.

- - -

Os astecas extirpavam correntemente, segundo se conta, em seus templos do sol oitenta mil crentes por semana, oferecendo-os assim ao Deus das nuvens, a fim de que lhes mandasse a chuva. São coisas em que a gente custa a crer antes de ir para a guerra. Mas quando aí estamos, tudo se explica, tantos os astecas quanto seu desprezo pelo corpo alheio, é o mesmo que devia ter por minhas humildes tripas o nosso general Céladon des Entrayes, supracitado, que se tornara por causa das promoções uma espécie de deus infalível, ele também uma espécie de pequeno sol de uma exigência atroz.

- - -

Nos enterros de luxo a gente também fica muito triste, mas mesmo assim pensa na herança, nas próximas férias, na viúva que é bonitinha e que é muito fogosa, dizem, e em ainda vivermos, nós mesmos, por contraste, muito tempo.

- - -

Quanto a mim, eu não tinha mais do que me queixar. Estava inclusive me alforriando graças à medalha militar que recebi, ao ferimento no braço e tudo. Em convalescença, tinham vindo me trazer a medalha, no próprio hospital. E no mesmo dia fui para o teatro, mostrá-la aos civis durante os intervalos. Grande efeito. Eram as primeiras medalhas que se viam em Paris.

- - -

Para mim, que esticava minha convalescença tanto quanto possível e que não fazia a menor questão de retomar meu turno no cemitério ardente das batalhas, o ridículo de nosso massacre me aparecia, barulhento, a cada passo que eu dava na cidade. Uma esperteza gigantesca espalhava-se por toda parte.

Entretanto, minhas chances de escapar eram poucas, eu não tinha nenhuma das relações indispensáveis para me safar da guerra. Só conhecia gente pobre, isto é, gente cuja morte não interessa a ninguém.

- - -

Daqui a alguns anos, aposto com você que esta guerra, tão notável quanto nos parece agora, estará totalmente esquecida... Mal-e-mal uma dúzia de eruditos ainda vão divergir aqui e acolá por causa dela e a propósito das datas das principais hecatombes que a ilustraram...

- - -

Quem pôde escapar vivo de um matadouro internacional em estado de demência tem afinal de contas um aprendizado no que se refere ao tato e à discrição.

Mais:

http://docs.google.com/file/d/0BxwrrqPyqsnIN0RDV012NnRERnc

http://docs.google.com/file/d/0BxwrrqPyqsnIS0ZTa1gwZlAybUk